Abstract

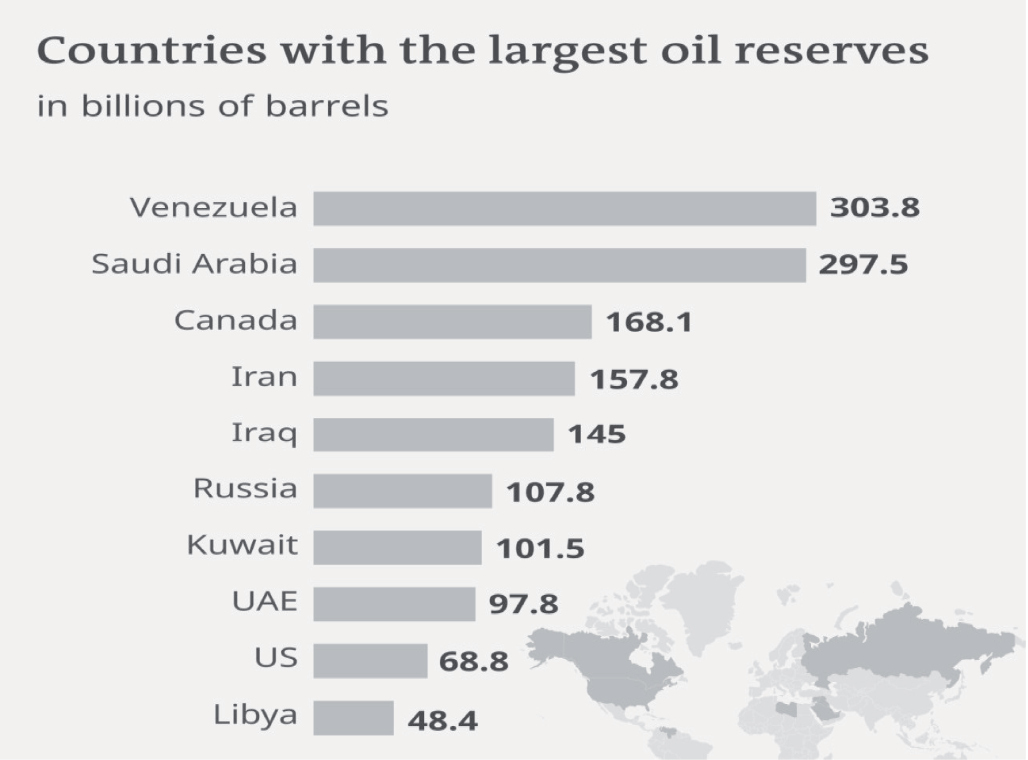

Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa have invited six other countries to join the BRICS grouping next year, namely Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. The expanded BRICS is the lynchpin of the changing world order and economic clout for the promotion of the Global South agenda. As evidence suggests, the new group is likely to exert profound influence over the world energy investment and trade: apart from impressive oil and gas deposits, an expanded BRICS could have 72 percent of rare earths (and three of the five countries with the largest reserves). This paper seeks to assess the energy market potential of each country invited to join the group and estimate the possible impact of these markets on mineral trade flows, investments, and energy trade deals within the BRICS association.

To address the implications for global energy markets carried by this expansion, the paper examines each new member of the BRICS grouping’s mineral supplies and renewable energy capabilities. The authors conduct qualitative data analysis based on numerical evidence collected from the energy sector reports of each country, the latest report of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and from publications by prominent experts of the countries invited to join BRICS. By revealing the current tendencies in BRICS oil and gas markets and the energy features peculiar to each of the new members, the paper answers the research question concerning the mineral resources that each new member of the bloc could offer in order to boost the BRICS energy markets. Touching upon the clean energy transition processes in the new member countries, the authors conclude by contemplating on the impact of the new BRICS on global energy trade in general.

To address the implications for global energy markets carried by this expansion, the paper examines each new member of the BRICS grouping’s mineral supplies and renewable energy capabilities. The authors conduct qualitative data analysis based on numerical evidence collected from the energy sector reports of each country, the latest report of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and from publications by prominent experts of the countries invited to join BRICS. By revealing the current tendencies in BRICS oil and gas markets and the energy features peculiar to each of the new members, the paper answers the research question concerning the mineral resources that each new member of the bloc could offer in order to boost the BRICS energy markets. Touching upon the clean energy transition processes in the new member countries, the authors conclude by contemplating on the impact of the new BRICS on global energy trade in general.

Introduction

The fifteenth BRICS summit, which took place in Johannesburg in August 2023, went down in history as the most representative annual meeting of the bloc, with 67 countries receiving the invitation to attend the summit and six of them approved as the new members. Reflecting a concerted effort to increase their global standing, BRICS countries signed an agreement to admit Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. Taking into account the energy potential of each member, the expansion of BRICS will most probably exert profound influence on energy investment and trade as it unites significant mineral resource holders and major oil producers, as well as some of the developing energy consumers.

Before its expansion, the bloc accounted for 36.4 percent of primary energy supply, having seen a sharp increase of 11.6 percent in global energy sector shares between the year of its formaton and 2022 (International Energy Agency, 2022). The concept of energy cooperation among the countries of BRICS revolved around producing and consuming, with Russia and Brazil boasting vast primary energy markets, and China and India importing their goods. The collective presence of the BRICS states in energy markets before its expansion was far from being ubiquitous (Qingxin & Zhongxiu, 2020): the group was not as largely engaged as it could have been. Considering the whole period of the group’s existence, its energy markets’ contribution has had low influence on investors’ behavior (Apergis & Payne, 2010). With the accession of new economies into the BRICS, however, its energy sector could potentially take center stage: each new member boasts substantial economic energy-related output, has various investment partners and possesses vast resources, both for traditional and alternative energy generation (Backaran & Cahill, 2023).

The authors will further elaborate on the influence of each new member on the energy trade between the countries of the bloc and assess its possible impact on the energy markets landscape within BRICS.

Before its expansion, the bloc accounted for 36.4 percent of primary energy supply, having seen a sharp increase of 11.6 percent in global energy sector shares between the year of its formaton and 2022 (International Energy Agency, 2022). The concept of energy cooperation among the countries of BRICS revolved around producing and consuming, with Russia and Brazil boasting vast primary energy markets, and China and India importing their goods. The collective presence of the BRICS states in energy markets before its expansion was far from being ubiquitous (Qingxin & Zhongxiu, 2020): the group was not as largely engaged as it could have been. Considering the whole period of the group’s existence, its energy markets’ contribution has had low influence on investors’ behavior (Apergis & Payne, 2010). With the accession of new economies into the BRICS, however, its energy sector could potentially take center stage: each new member boasts substantial economic energy-related output, has various investment partners and possesses vast resources, both for traditional and alternative energy generation (Backaran & Cahill, 2023).

The authors will further elaborate on the influence of each new member on the energy trade between the countries of the bloc and assess its possible impact on the energy markets landscape within BRICS.

Argentina

Although Javier Milei’s administration has rejected the invitation to the BRICS grouping in 2023, the authors will still include Argentina’s energy potential in their research analysis. Judging by the social unrest caused by radical economic reforms of Javier Milei’s cabinet, it is likely that Argentina will soon see the accession to power of the new administration, which may return to the idea of joining BRICS.

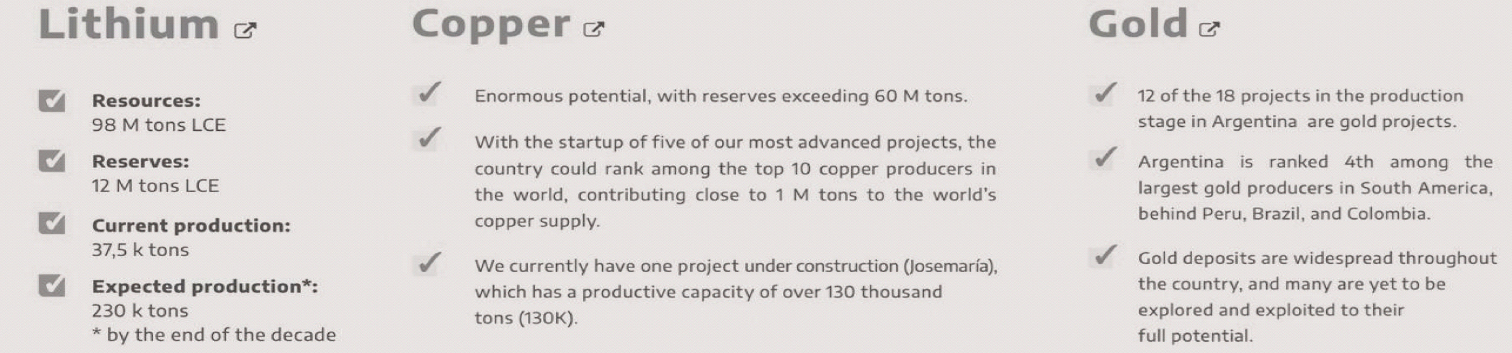

Boasting the world’s second reserves and being the third largest producer, Argentina is also a promising supplier of lithium, as it possesses a number of strong lithium projects. According to JP Morgan estimates, Argentina is bound to surpass China (Hooijmaaijers, 2021) and Chile in global lithium production by 2027. Argentina’s vast lithium deposits could potentially make a difference for the energy markets of the bloc: along with China and Brazil (Hooijmaaijers, 2021), the admission of Argentina would give the BRICS group three of the top five lithium producers in the world.

What is more, being the third lithium producer on a global scale, Argentina is yet to unlock its potential for exporting other minerals, that amounts to 65 million tons of copper, 61.4 tons of gold, and 802 billion cubic feet of shale gas (10.5% of the world’s resources). It is anticipated that mineral export revenue will reach US$10 billion annually with the aid of BRICS members.

Boasting the world’s second reserves and being the third largest producer, Argentina is also a promising supplier of lithium, as it possesses a number of strong lithium projects. According to JP Morgan estimates, Argentina is bound to surpass China (Hooijmaaijers, 2021) and Chile in global lithium production by 2027. Argentina’s vast lithium deposits could potentially make a difference for the energy markets of the bloc: along with China and Brazil (Hooijmaaijers, 2021), the admission of Argentina would give the BRICS group three of the top five lithium producers in the world.

What is more, being the third lithium producer on a global scale, Argentina is yet to unlock its potential for exporting other minerals, that amounts to 65 million tons of copper, 61.4 tons of gold, and 802 billion cubic feet of shale gas (10.5% of the world’s resources). It is anticipated that mineral export revenue will reach US$10 billion annually with the aid of BRICS members.

Considering the partnership tendencies between the BRICS countries in the energy sector (Wilson, 2015), Argentina’s entrance to the bloc will be of particular importance to such countries as Brazil, China and Russia. In 2023, Brazil and Argentina formally adopted a cooperative 100-projects development action plan to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the two nations’ diplomatic ties; one of these projects involves the expansion of the Argentinian gas pipeline. With Brazil’s support, in 2024 Argentina is likely to succeed in attracting more investments from the BRICS countries: China has already endorsed a structured investment plan of US$100 billion in Argentina’s lithium production. Argentina is also of interest to Russia: in order to create a joint venture to develop the Tolillar lithium deposit in Argentina, Alpha Lithium Corporation and Uranium One Holding N. V., a Rosatom business, entered into an agreement in November 2021. Therefore, Argentina’s admission to BRICS will boost intra-BRICS trade, pushing its 2022 record of US$8,5 trillion even further. What is more, the membership in BRICS will substantially benefit the country’s economic landscape as it is now struggling with high inflation rates, constant peso devaluation and rising unemployment.

Apart from giving impulse to mutual trade between the countries of the bloc, Argentina’s lithium resources will help BRICS’ energy markets stand out on a global scale. As the world is trying to meet the rising demand for sustainable energy and electric vehicle batteries, lithium’s strategic significance will increase. These tendencies suggest that the expanded BRICS lithium market may bring about significant gains in the future, which will probably lead to a new wave of geopolitical rivalry. Also, lithium is part of the clean energy agenda the world is striving for: its significance as a strategic mineral will grow exponentially as the effects of climate change spread throughout the world, eventually becoming an essential component for future clean energy systems.

These developments do not mean that BRICS will reach an OPEC-like ability to control global prices. Yet its expansion guarantees an increase in influence over global energy markets (Backaran & Cahill, (2023), with Argentina being part of this trend.

Apart from giving impulse to mutual trade between the countries of the bloc, Argentina’s lithium resources will help BRICS’ energy markets stand out on a global scale. As the world is trying to meet the rising demand for sustainable energy and electric vehicle batteries, lithium’s strategic significance will increase. These tendencies suggest that the expanded BRICS lithium market may bring about significant gains in the future, which will probably lead to a new wave of geopolitical rivalry. Also, lithium is part of the clean energy agenda the world is striving for: its significance as a strategic mineral will grow exponentially as the effects of climate change spread throughout the world, eventually becoming an essential component for future clean energy systems.

These developments do not mean that BRICS will reach an OPEC-like ability to control global prices. Yet its expansion guarantees an increase in influence over global energy markets (Backaran & Cahill, (2023), with Argentina being part of this trend.

Egypt

Another country which has joined BRICS amidst hopes for foreign direct investment to bolster its economic growth is Egypt, one of the three representatives of the Arab world in the BRICS association alongside Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The principal objective Egypt is striving to meet as a new member of the bloc is, understandably, easier access to economic and financial aid as the country is being mired in economic crisis of 36.5% inflation rate and US$165 billion foreign debt. Another prospect that garnered Egypt’s specific attention is the dedollarization initiative as a measure against a 50% drop of the Egyptian Pound to the US dollar. According to Egyptian analysts, the country’s participation in BRICS will lead to US$25 billion savings as a result of an increased use of its own currency when importing goods from the BRICS group. Despite Egypt’s current unstable economic situation, its membership is highly beneficial to BRICS, especially to its energy sector, for several reasons.

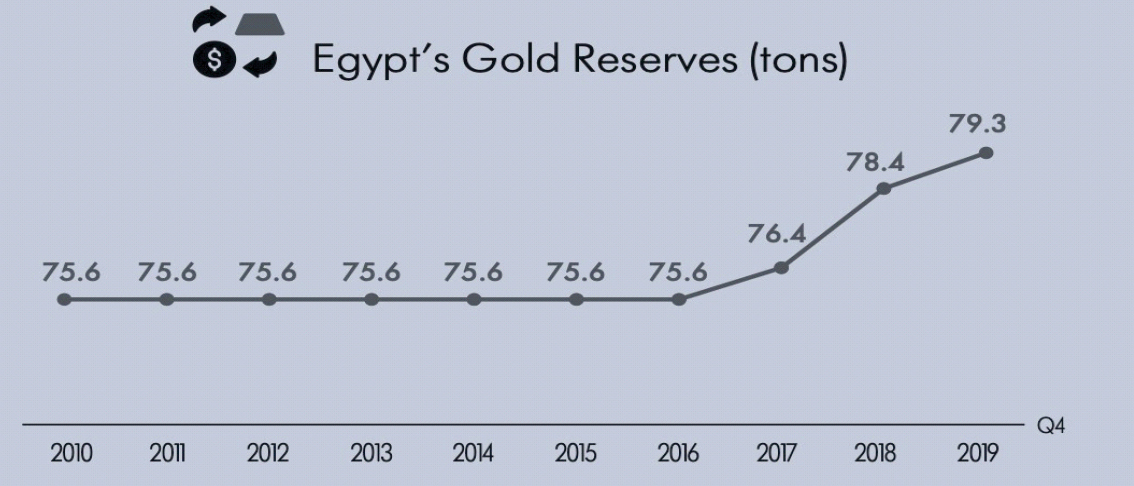

First, Egypt is the largest non-OPEC oil producer in Africa and the second largest gas producer on the continent, with its total proven oil reserves of 4.4 billion barrels and natural gas reserves of 63 trillion cubic feet. Apart from this, Egypt boasts 48 million tons (mmt) of tantalite, making it straight to the top-4 largest producers, and possesses 79.45 million tons of gold and 18 million tons of coal6. BRICS membership is likely to trigger upstream investment for Egypt: its vast mineral resources could possibly attract investors from China and India. Being of particular interest, Egypt’s tantalite will bolster BRICS electronics, pigments, medical, aerospace, defense and chemical processing industries, benefiting BRICS as a whole.

The principal objective Egypt is striving to meet as a new member of the bloc is, understandably, easier access to economic and financial aid as the country is being mired in economic crisis of 36.5% inflation rate and US$165 billion foreign debt. Another prospect that garnered Egypt’s specific attention is the dedollarization initiative as a measure against a 50% drop of the Egyptian Pound to the US dollar. According to Egyptian analysts, the country’s participation in BRICS will lead to US$25 billion savings as a result of an increased use of its own currency when importing goods from the BRICS group. Despite Egypt’s current unstable economic situation, its membership is highly beneficial to BRICS, especially to its energy sector, for several reasons.

First, Egypt is the largest non-OPEC oil producer in Africa and the second largest gas producer on the continent, with its total proven oil reserves of 4.4 billion barrels and natural gas reserves of 63 trillion cubic feet. Apart from this, Egypt boasts 48 million tons (mmt) of tantalite, making it straight to the top-4 largest producers, and possesses 79.45 million tons of gold and 18 million tons of coal6. BRICS membership is likely to trigger upstream investment for Egypt: its vast mineral resources could possibly attract investors from China and India. Being of particular interest, Egypt’s tantalite will bolster BRICS electronics, pigments, medical, aerospace, defense and chemical processing industries, benefiting BRICS as a whole.

Second, Egypt is one of the Arab world leaders in clean energy transition, intending to increase the supply of electricity generated from renewable sources to 60% by 2040. To achieve this, the government has already initiated a number of energy sector reforms, gradually reducing electricity subsidies and introducing feed-in tariffs to promote renewable energy production. While the renewable energy consumption of BRICS countries only accounts for 16 percent (Yu et al., 2019), Egypt’s experience in this field should accelerate clean energy transition in the other BRICS member states.

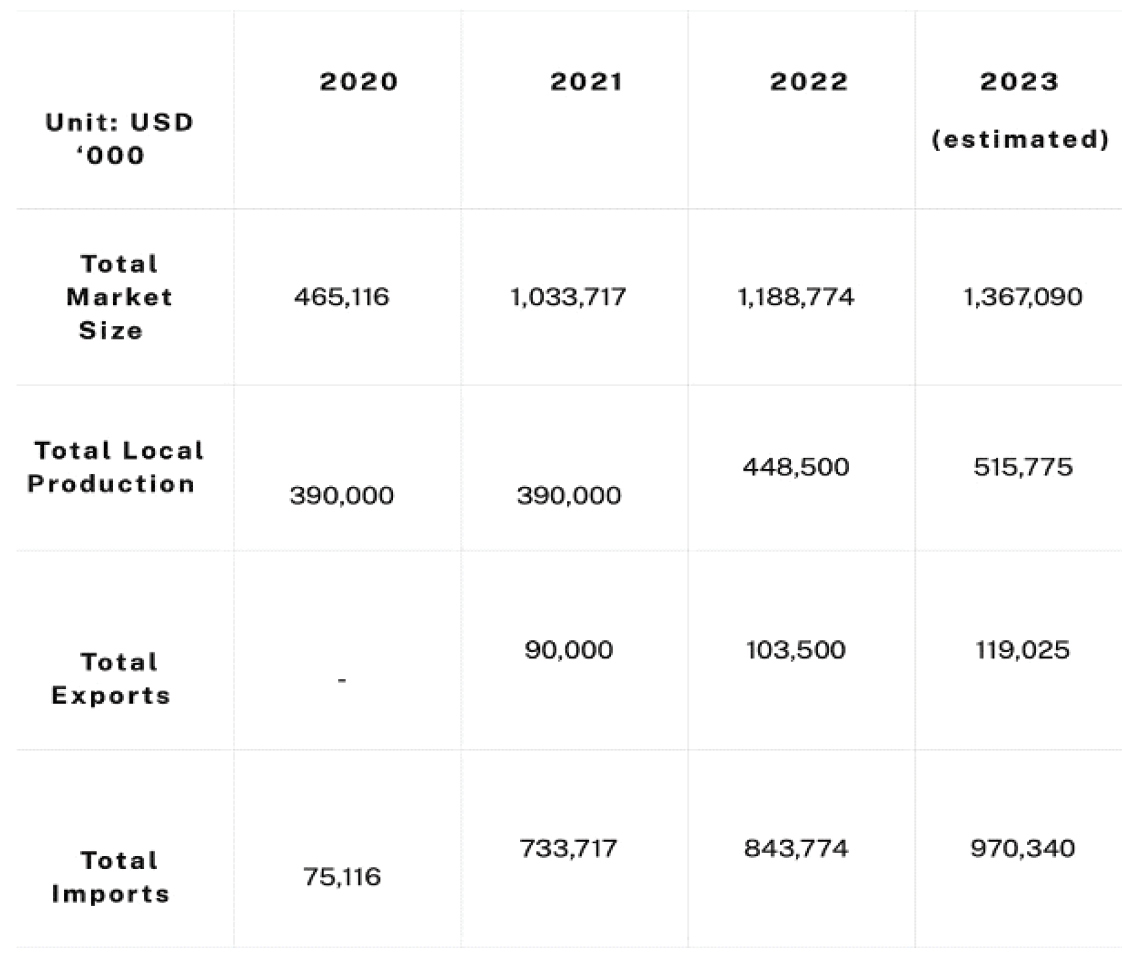

Third, Egypt will significantly boost mutual trade inside the BRICS group. Egypt’s amounts of trade with the BRICS members, particularly with Russia, China, and India, are rather impressive. By taking advantage of trade agreements such as the Common Market of the South (Mercosur) and thus expanding its exports, Egypt could potentially serve as a hub for connecting Africa, Asia, and South America (Liu et al., 2022).

In 2022, trade between Egypt and the BRICS nations reached $31.2 billion, showing a 10.5% surge from $28.3 billion in 2021. Provided Egypt achieves its long-term goal of US$100 billion in annual exports, the admission of Egypt to BRICS may contribute to an increase in the group’s geopolitical weight. Russia sought Egypt’s inclusion to counterbalance the Chinese initiative to accept Ethiopia. In particular, Moscow is discussing with Cairo the establishment of a special economic zone in the vicinity of the Suez Canal.

Egypt’s accession to BRICS opens decent economic and energetic prospects for the other members of the group, positively impacting both tradition and renewable energy markets. In 2024, Egypt and BRICS are exploring ways to enhance cooperation between the Egyptian electricity and renewable energy sector and banking. Specifically, Mohamed Shaker, the Minister of Electricity and Renewable Energy, declared that negotiations are underway with BRICS investors for competitive solar energy projects, with rates of 2 cents per kilowatt-hour for solar projects and 2.45 cents per kilowatt-hour for wind projects. Global players’ appetite for Egyptian projects is evident: the country is seen as a gateway to the African continent.

Third, Egypt will significantly boost mutual trade inside the BRICS group. Egypt’s amounts of trade with the BRICS members, particularly with Russia, China, and India, are rather impressive. By taking advantage of trade agreements such as the Common Market of the South (Mercosur) and thus expanding its exports, Egypt could potentially serve as a hub for connecting Africa, Asia, and South America (Liu et al., 2022).

In 2022, trade between Egypt and the BRICS nations reached $31.2 billion, showing a 10.5% surge from $28.3 billion in 2021. Provided Egypt achieves its long-term goal of US$100 billion in annual exports, the admission of Egypt to BRICS may contribute to an increase in the group’s geopolitical weight. Russia sought Egypt’s inclusion to counterbalance the Chinese initiative to accept Ethiopia. In particular, Moscow is discussing with Cairo the establishment of a special economic zone in the vicinity of the Suez Canal.

Egypt’s accession to BRICS opens decent economic and energetic prospects for the other members of the group, positively impacting both tradition and renewable energy markets. In 2024, Egypt and BRICS are exploring ways to enhance cooperation between the Egyptian electricity and renewable energy sector and banking. Specifically, Mohamed Shaker, the Minister of Electricity and Renewable Energy, declared that negotiations are underway with BRICS investors for competitive solar energy projects, with rates of 2 cents per kilowatt-hour for solar projects and 2.45 cents per kilowatt-hour for wind projects. Global players’ appetite for Egyptian projects is evident: the country is seen as a gateway to the African continent.

Ethiopia

Despite the unexpected character of the country’s accession to BRICS, Ethiopia is as poised to assist in boosting the bloc’s economic growth as the other members. Being the sixth largest African economy, over the past 15 years, Ethiopia’s economy has been growing at an average 10% annually. With the 2022 GDP growth rate of 6.6% and continuously increasing exports (International Energy Agency, 2022), Ethiopia may contribute to the success of the BRICS group. The Ethiopian government has made tangible efforts in terms of energy policy and strategy formulation over the past 20 years and today it recognizes the crucial role of the energy sector in meeting the nation’s economic aspirations.

Ethiopia boasts considerable potential pertaining to its renewable energy facilities: the country is able to generate over 60, 000 megawatts (MW) of electricity from hydroelectric, wind, solar, and geothermal sources. Hydropower accounts for about 90% of the installed generation capacity, while wind and thermal sources account for 8% and 2%, respectively9. The demand for electricity has been steadily rising as a result of Ethiopia’s quick GDP growth over the previous ten years. Taking into account the BRICS countries’ rising interest in clean energy transition (Razzaq et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2019) Ethiopia’s fast-growing renewable energy sector may be a good example for other BRICS members to follow. The members of the association may work on joint projects in the sphere of alternative energy and, with the help of Ethiopia, build a more structured and cooperative response to the changing landscape of global energy markets.

It is also important that Ethiopia possesses vast mineral resources. Covering 20% of Ethiopia’s land area, the Abbai River basin holds significant deposits, over 265 of which are 190 metallic including (gold, iron, copper, zinc) and over 75 are non-metallic (limestone, marble, lignite). Ethiopia boasts one of the world’s oldest and yet untapped gold deposits of 200 tons10. The gold mining sector also creates employment and, therefore, supports the livelihood of millions of Ethiopians.

Ethiopia boasts considerable potential pertaining to its renewable energy facilities: the country is able to generate over 60, 000 megawatts (MW) of electricity from hydroelectric, wind, solar, and geothermal sources. Hydropower accounts for about 90% of the installed generation capacity, while wind and thermal sources account for 8% and 2%, respectively9. The demand for electricity has been steadily rising as a result of Ethiopia’s quick GDP growth over the previous ten years. Taking into account the BRICS countries’ rising interest in clean energy transition (Razzaq et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2019) Ethiopia’s fast-growing renewable energy sector may be a good example for other BRICS members to follow. The members of the association may work on joint projects in the sphere of alternative energy and, with the help of Ethiopia, build a more structured and cooperative response to the changing landscape of global energy markets.

It is also important that Ethiopia possesses vast mineral resources. Covering 20% of Ethiopia’s land area, the Abbai River basin holds significant deposits, over 265 of which are 190 metallic including (gold, iron, copper, zinc) and over 75 are non-metallic (limestone, marble, lignite). Ethiopia boasts one of the world’s oldest and yet untapped gold deposits of 200 tons10. The gold mining sector also creates employment and, therefore, supports the livelihood of millions of Ethiopians.

Ethiopia’s government has recently developed the second Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP II), aimed at enhancing the performance of the energy export sector. Given Ethiopia’s infrastructure-based growth model, public investment by BRICS members will spur economic growth in 2024– 2027, which aligns with the goals of the group.

It was expected that Ethiopia’s membership received strong support from China which had been increasing its presence in the country via China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and the Belt and Road Initiative. More specifically, China’s imports from Ethiopia amounted to US$52.5 million in May 2023, indicating a rise in bilateral trade from US$ 2.95 billion in 2021 to US$ 3.3 billion by 2023. Ethiopia’s joining the BRICS group will contribute to strengthening Ethiopian-Chinese relations, increasing intra-BRICS trade. What is more, the country’s presence in BRICS can be an opportunity for the development of trade with new members which represent fast-growing economies, such as the three Arab countries. Being part of BRICS, the country is also seeking advantage in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) in renewable energy transition projects.

Finally, BRICS will benefit from Ethiopia’s labor and export manufacturing potential, with almost 50% of its population being under 18 and the young work force of sufficient size. Ethiopia could potentially participate in the cultural initiatives of the BRICS group by encouraging young people to participate in the BRICS countries educational exchange programs.

It was expected that Ethiopia’s membership received strong support from China which had been increasing its presence in the country via China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and the Belt and Road Initiative. More specifically, China’s imports from Ethiopia amounted to US$52.5 million in May 2023, indicating a rise in bilateral trade from US$ 2.95 billion in 2021 to US$ 3.3 billion by 2023. Ethiopia’s joining the BRICS group will contribute to strengthening Ethiopian-Chinese relations, increasing intra-BRICS trade. What is more, the country’s presence in BRICS can be an opportunity for the development of trade with new members which represent fast-growing economies, such as the three Arab countries. Being part of BRICS, the country is also seeking advantage in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) in renewable energy transition projects.

Finally, BRICS will benefit from Ethiopia’s labor and export manufacturing potential, with almost 50% of its population being under 18 and the young work force of sufficient size. Ethiopia could potentially participate in the cultural initiatives of the BRICS group by encouraging young people to participate in the BRICS countries educational exchange programs.

Iran

Among the six newly invited nations, the accession of Iran to the BRICS group holds a unique significance, as a means of breaking the country’s isolation on the international arena. Should Iran’s membership in the BRICS come to fruition, it could gain significant advantages on two fronts. From a political perspective, Iran’s legitimacy — which was severely damaged by the massive uprising last year — could be restored, at least to some extent. From an economic perspective, the Iranian government could have an opportunity to improve trade ties with the BRICS member states, contributing to an increase in the intra-BRICS trade.

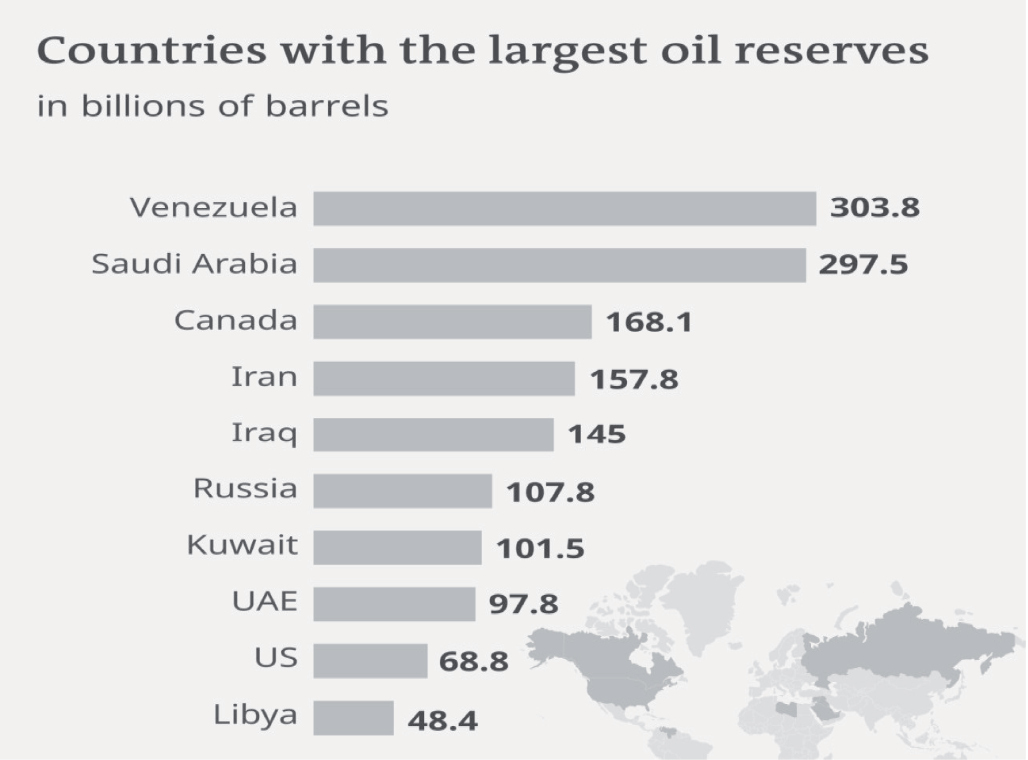

Petroleum industry is a key sector of the Iranian’s economy, with Iran’s oil reserves ranking the fourth in the world and accounting for about 9.5% of the world’s total deposits. Alongside oil Iran holds some of the largest natural gas reserves, amounting to 12% of the world’s total reserves and pushing the country to the top three natural gas holders. The country has 68 different minerals with reserves totaling 43 billion tons worth an estimated $700 billion, according to Iran’s state-owned mines and metal holding company IMIDRO. Among those riches the main minerals are gold, copper, steel, zinc and iron ore. Also, Iran is yet to unlock its renewable energy potential (Valizadeh & Houshialsadat, 2013): Different regions of Iran have high wind, solar and geothermal energy potential13. The admission of Iran to BRICS will pave the way for the development of the Iranian energy markets, which will be beneficial both for Iran and the BRICS countries. Moreover, it is expected that Iran’s membership will contribute to meeting the growing energy needs of the BRICS member states (Valizadeh & Houshialsadat, 2013).

The admission of Iran to BRICS stems from a profound Russian-Chinese consensus: having a strategic partnership with Beijing and Moscow, Tehran seeks to bolster economic transactions with them in non-dollar currencies. More than that, by developing intra-BRICS ties Iran will push further the US sanctions: Washington will face significant difficulties enforcing sanctions on a number of countries once they have entered into trade with Iran because of BRICS collectively making up almost half of the global population. Also, Iran has a chance to strengthen its ties with the other two Persian Gulf energy powers that entered the BRICS grouping, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In particular, in spring-summer 2023 both Tehran and Riyadh formally restored diplomatic relations which marked significant strides toward full reconciliation, with China being the driving force behind Middle East peace process.

Petroleum industry is a key sector of the Iranian’s economy, with Iran’s oil reserves ranking the fourth in the world and accounting for about 9.5% of the world’s total deposits. Alongside oil Iran holds some of the largest natural gas reserves, amounting to 12% of the world’s total reserves and pushing the country to the top three natural gas holders. The country has 68 different minerals with reserves totaling 43 billion tons worth an estimated $700 billion, according to Iran’s state-owned mines and metal holding company IMIDRO. Among those riches the main minerals are gold, copper, steel, zinc and iron ore. Also, Iran is yet to unlock its renewable energy potential (Valizadeh & Houshialsadat, 2013): Different regions of Iran have high wind, solar and geothermal energy potential13. The admission of Iran to BRICS will pave the way for the development of the Iranian energy markets, which will be beneficial both for Iran and the BRICS countries. Moreover, it is expected that Iran’s membership will contribute to meeting the growing energy needs of the BRICS member states (Valizadeh & Houshialsadat, 2013).

The admission of Iran to BRICS stems from a profound Russian-Chinese consensus: having a strategic partnership with Beijing and Moscow, Tehran seeks to bolster economic transactions with them in non-dollar currencies. More than that, by developing intra-BRICS ties Iran will push further the US sanctions: Washington will face significant difficulties enforcing sanctions on a number of countries once they have entered into trade with Iran because of BRICS collectively making up almost half of the global population. Also, Iran has a chance to strengthen its ties with the other two Persian Gulf energy powers that entered the BRICS grouping, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In particular, in spring-summer 2023 both Tehran and Riyadh formally restored diplomatic relations which marked significant strides toward full reconciliation, with China being the driving force behind Middle East peace process.

Apart from the rewards to be reaped from cooperation between Iran and other BRICS countries, Iran’s accession may have a profound impact on its foreign policy. In recent years, Iran’s government has clearly shifted the focus from isolation to forming alliances in an attempt to counterbalance the powers of the Western world. Iran’s interest in BRICS goes further than promoting its economic growth: together with China and Russia Iran seeks to launch a new thinking perspective, seeing BRICS not only as a platform for dialogue but rather as an alternative to the Western organizations, such as G7. In turn, Iran seems willing to share its vast mineral reserves and renewable energy resources with other members of the association, thus putting in more geopolitical weight in the energy sector and intra-BRICS trade.

A larger BRICS grouping may also see an increase in investments in projects and places that non-partner countries would avoid. Iran is a good example. Despite possessing significant amounts of critical minerals, Iran has been unable to mobilize investment to increase production due to rigid economic sanctions (another 17 Iranian mining companies were sanctioned in 2020) (International Energy Agency, 2020). Now in due course, one can expect investment flowing into Iran in exchange for copper, zinc, and lithium.

A larger BRICS grouping may also see an increase in investments in projects and places that non-partner countries would avoid. Iran is a good example. Despite possessing significant amounts of critical minerals, Iran has been unable to mobilize investment to increase production due to rigid economic sanctions (another 17 Iranian mining companies were sanctioned in 2020) (International Energy Agency, 2020). Now in due course, one can expect investment flowing into Iran in exchange for copper, zinc, and lithium.

Saudi Arabia

The largest Arab economy with an annual GDP of over $1 trillion, Saudi Arabia remains the most powerful new member of the BRICS association. It is one of the most significant players on the global oil market, responsible for approximately 15% of the world’s proven oil reserves. While Argentina, Ethiopia, Egypt and Iran entered the group seeking financial aid, Saudi Arabia’s main motive is to exploit deeper engagement with fast-growing economies and increase exports to new markets.

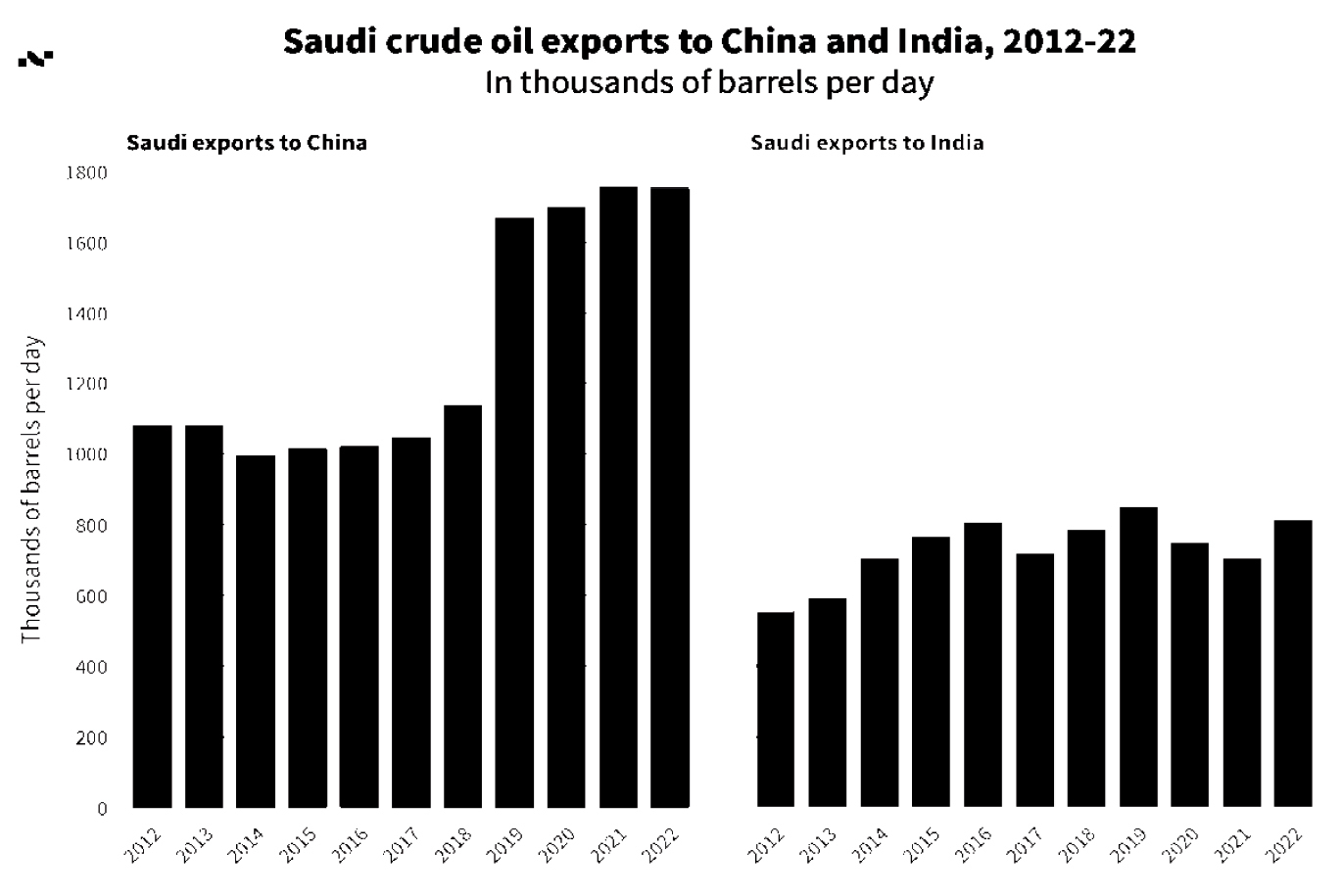

Following the agenda of “Look East” policy, Saudi Arabia’s government seems to be especially interested in fostering cooperation with Asian states, such as China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, that account for most of the global demand for Gulf oil and gas. In particular, Saudi Arabia focuses on exporting vast amounts of oil and gas to China and India to capitalize on anticipated economic growth in Asia amid technological innovation (Liu et al., 2022).

Following the agenda of “Look East” policy, Saudi Arabia’s government seems to be especially interested in fostering cooperation with Asian states, such as China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, that account for most of the global demand for Gulf oil and gas. In particular, Saudi Arabia focuses on exporting vast amounts of oil and gas to China and India to capitalize on anticipated economic growth in Asia amid technological innovation (Liu et al., 2022).

Saudi Arabia’s accession to the grouping could also be interpreted as a signal to the US policy makers about the intentions of Saudi Arabia to diversify its alliances instead of falling back on the partnership only with the Western world. The reason behind this shift of priorities in the country’s foreign policies could partly be explained by the US “exit strategy” which implies its gradual withdrawal from the Middle East. Despite its strong ties with the USA, Saudi Arabia is engaged in de-dollarization activities promoted by the BRICS countries. It has already conducted trade transactions in its local currency, albeit on a small scale. Saudi Arabia favors reducing dollar payments and is likely to promote this initiative in the group, also enjoying support of the United Arab Emirates. The country seeks to improve its relations with Russia: the two countries together account for a quarter of the world’s oil production.

Energy markets form the basis of Saudi Arabia’s successful membership in BRICS. Under the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman the country is striving to a more open and diversified economy. As part of the Vision 2030 plan, this ambition is mainly financed by revenues from oil, gas, and mineral resources, such as coal, copper, zinc, uranium and gold.

Despite its heavy reliance on the traditional energy markets, Saudi Arabia has ambitious goals in renewable energy sector. For instance, by 2030 the country plans to get 50% of its electricity from renewable sources. Being the largest operator of electricity generation plants, Saudi company ACWA Power has launched a solar plant project, which will be one of the largest single-contracted solar PV plants in the world, with an installed capacity of 1,500 megawatts capable of powering 185,000 homes and offsetting nearly 2.9 million tons of emissions each year14. As well as complying with its domestic targets, Saudi Arabia strives to export its renewable energy potential to other fast-growing economies. In particular, the country is currently engaged in projects with 10 countries, including two other Persian Gulf states — Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

Energy markets form the basis of Saudi Arabia’s successful membership in BRICS. Under the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman the country is striving to a more open and diversified economy. As part of the Vision 2030 plan, this ambition is mainly financed by revenues from oil, gas, and mineral resources, such as coal, copper, zinc, uranium and gold.

Despite its heavy reliance on the traditional energy markets, Saudi Arabia has ambitious goals in renewable energy sector. For instance, by 2030 the country plans to get 50% of its electricity from renewable sources. Being the largest operator of electricity generation plants, Saudi company ACWA Power has launched a solar plant project, which will be one of the largest single-contracted solar PV plants in the world, with an installed capacity of 1,500 megawatts capable of powering 185,000 homes and offsetting nearly 2.9 million tons of emissions each year14. As well as complying with its domestic targets, Saudi Arabia strives to export its renewable energy potential to other fast-growing economies. In particular, the country is currently engaged in projects with 10 countries, including two other Persian Gulf states — Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

The United Arab Emirates

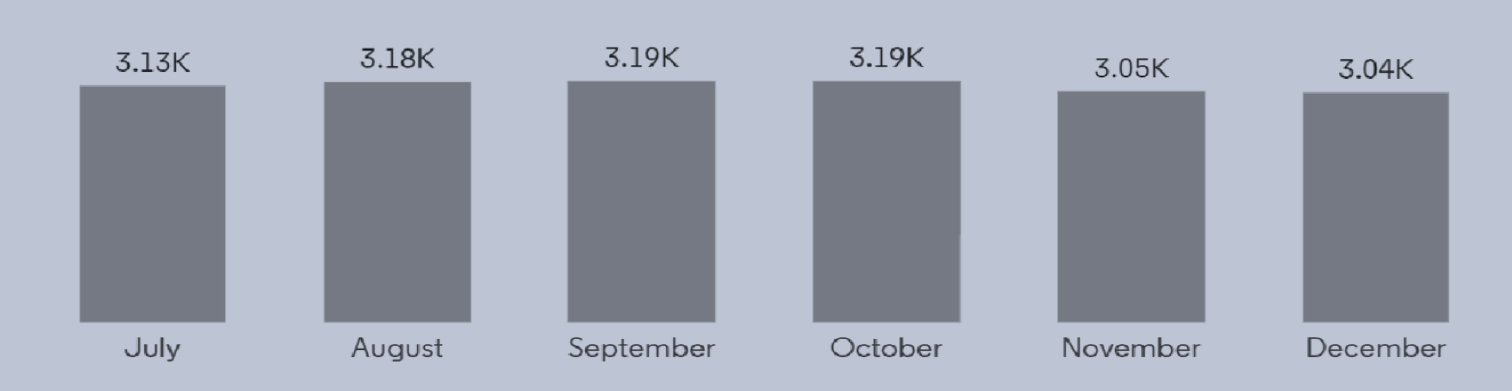

With its oil reserves reaching 107 billion barrels, the United Arab Emirates has become one of the three Persian Gulf energy powers to be invited to the BRICS bloc. Boasting vast oil deposits, the UAE occupies the 8th place in the world’s top-10 largest oil producers ranking. The UAE produce an average of 3.2 million barrels of petroleum and liquids per day.

The country also holds the seventh-largest proven reserves of natural gas in the world of over 215 trillion cubic feet. In 2020, the UAE announced the discovery of more than 80 trillion cubic feet of gas resources at Jebel Ali (International Energy Agency, 2020). The UAE also possess large aluminum deposit (the 5th place in the world). This enormous energy potential is key factor driving the United Arab Emirates’ plans to boost cooperation with their eastern partners, China and India, the major importers of mineral resources.

The country also holds the seventh-largest proven reserves of natural gas in the world of over 215 trillion cubic feet. In 2020, the UAE announced the discovery of more than 80 trillion cubic feet of gas resources at Jebel Ali (International Energy Agency, 2020). The UAE also possess large aluminum deposit (the 5th place in the world). This enormous energy potential is key factor driving the United Arab Emirates’ plans to boost cooperation with their eastern partners, China and India, the major importers of mineral resources.

Apart from the traditional energy sector, the UAE has recently revealed its ambitions to triple the contribution of the renewable energy in the economy in accordance with the provisions of The UAE Energy Strategy 2050 (Liu et al., 2022). By 2050, the UAE intends to use 44% renewable energy, 38% gas, 12% clean coal, and 6% nuclear energy sources to produce half of its electricity. The vehicle park will soon be electrified: the UAE expects to have 40.000 electric vehicles on its roads by 2030. Also, the country is planning to invest up to $54 billion over the next seven years to meet its clean energy transition aspirations.

The United Arab Emirates envision their participation in the BRICS grouping as part of their economic growth strategy. In particular, the country has set an ambitious goal to double its GDP to over $800 billion by the end of 2023, and its alignment with China and India can significantly contribute to such aspirations. In 2022, bilateral trade between China and the UAE grew by 28 percent, or $64 billion. Similar to this, between April 2022 and March 2023, bilateral trade between the UAE and India totaled $84.5 billion. Also, the UAE has embraced the de-dollarization initiatives of the BRICS grouping. For instance, in July 2023 the UAE and India agreed on settling trade in rupees instead of dollars, boosting India’s efforts to cut transaction costs by eliminating dollar conversions. The first transactions between the two countries under the new agreement, including in oil and gold, have already commenced. This historic agreement between the UAE and India could encourage other BRICS members to follow suit in 2024. As well as receiving more access to partnership with China and India, the United Arab Emirates is seeking to explore new markets, such as Russia (8th largest GDP), Brazil (11th) and Argentina (22nd). The bilateral trade between the UAE and Russia grew by 68% in 2022 to a record $9 billion, of which Russian exports made up $8.5 billion, i.e. a 71% increase. In 2022, gold and precious stones constituted almost 40% of Russian exports to the UAE.

Moreover, as a participant of the New Development Bank (BRICS), the United Arab Emirates is poised to provide new BRICS members, such as Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Iran, with financial resources for their infrastructure projects. Since its establishment six years ago, NDB has approved about 80 projects in its member countries, totaling a portfolio of US$ 30 billion. Projects in areas such as transport, water and sanitation, clean energy, digital infrastructure, social infrastructure and urban development are within the scope of the Bank. The accession of the UAE to BRICS and its participation in NDB will push further its financial capabilities to assist in boosting the new members’ economic growth.

The United Arab Emirates envision their participation in the BRICS grouping as part of their economic growth strategy. In particular, the country has set an ambitious goal to double its GDP to over $800 billion by the end of 2023, and its alignment with China and India can significantly contribute to such aspirations. In 2022, bilateral trade between China and the UAE grew by 28 percent, or $64 billion. Similar to this, between April 2022 and March 2023, bilateral trade between the UAE and India totaled $84.5 billion. Also, the UAE has embraced the de-dollarization initiatives of the BRICS grouping. For instance, in July 2023 the UAE and India agreed on settling trade in rupees instead of dollars, boosting India’s efforts to cut transaction costs by eliminating dollar conversions. The first transactions between the two countries under the new agreement, including in oil and gold, have already commenced. This historic agreement between the UAE and India could encourage other BRICS members to follow suit in 2024. As well as receiving more access to partnership with China and India, the United Arab Emirates is seeking to explore new markets, such as Russia (8th largest GDP), Brazil (11th) and Argentina (22nd). The bilateral trade between the UAE and Russia grew by 68% in 2022 to a record $9 billion, of which Russian exports made up $8.5 billion, i.e. a 71% increase. In 2022, gold and precious stones constituted almost 40% of Russian exports to the UAE.

Moreover, as a participant of the New Development Bank (BRICS), the United Arab Emirates is poised to provide new BRICS members, such as Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Iran, with financial resources for their infrastructure projects. Since its establishment six years ago, NDB has approved about 80 projects in its member countries, totaling a portfolio of US$ 30 billion. Projects in areas such as transport, water and sanitation, clean energy, digital infrastructure, social infrastructure and urban development are within the scope of the Bank. The accession of the UAE to BRICS and its participation in NDB will push further its financial capabilities to assist in boosting the new members’ economic growth.

Conclusion

The expansion of BRICS will have a profound impact on both traditional energy markets, largely represented by oil and natural gas, and renewable energy initiatives. The new BRICS brings together large mineral resource holders and major oil producers, as well as some of the fastest growing energy consumers. An expanded BRICS association can have 72% of rare earths (and three of the five countries with the largest reserves). The expanded bloc would also hold 75% of world’s manganese, 50% of the world’s graphite, 28% of the world’s nickel, and 19% of the world’s copper (Backaran & Cahill, 2023).

The accession of Argentina will strengthen the group’s lithium supplies. Gulf powers rely heavily on investments in lithium, with Saudi Arabia having bought Brazil’s largest mining company Vale. It is expected that in their attempt to search for the new fast-growing markets Saudi Arabia along with the United Arab Emirates will invest into Argentina’s lithium. The BRICS countries’ plans to invest in Argentina’s mineral potential may cause its new president Javier Milei to reconsider the decision about leaving the group in accordance with his promises during the electoral campaign.

The membership of African nations, such as Egypt and Ethiopia, in the BRICS grouping is sure to have geopolitical consequences. From the political perspective, the expanded BRICS should serve as an effective tool for Africa to gain meaningful representation on international platforms. From the economic perspective, Egypt and Ethiopia’s huge mineral resources (oil, gas, gold, tantalite, copper, zinc) and renewable energy potential are likely to attract investment flows from the traditional Asian importers, China and India, and Persian energy powers, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Kairo is more likely to foster bilateral ties with Moscow, while Addis Ababa favors Chinese presence in its infrastructure projects.

Iran’s invitation to BRICS has a particular significance as it implies the possibility of BRICS becoming an alternative to the Western Bretton-Woods organizations. Having received a warm welcome, especially from Russia and China, Iran’s membership in BRICS will help it restore the diversity of its foreign policy through its rich natural resources (oil, gas, gold, steel, copper, iron ore) as a means to counterbalance the US sanctions.

The presence of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in BRICS is crucial, as these countries represent the strongest economies invited to join the group. They are particularly interested in boosting cooperation with dynamically growing China and India and having new markets to invest in, such as Russia, Brazil and the African nations. These countries are willing to support the BRICS de-dollarization initiatives to conduct trade in their own currencies. The agreement between India and the UAE will encourage other members to follow suit. Overall, with the addition of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran, this expanded group will include three of the world’s largest oil exporters and have 42% of global oil supply.

Oil market management will remain the purview of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and allied producers (OPEC+). In the long term, however, an expanded BRICS grouping could also play a role (Qingxin & Zhongxiu, 2020). For years, OPEC+ states have claimed that Western energy sanctions on Iran and Venezuela constrain investment and export flows. More recently, the EU embargoes on Russian seaborne crude oil and petroleum products and the EU-G7 price caps have created a new sanctions mechanism that targets revenues rather than export volumes. Other exporters worry that new sanctions tools could target them in the future, and they are wary of G7 interventions that have reshaped energy flows.

An enlarged BRICS will include oil and gas exporters and two of the largest importers, China and India—both of which refused to join the sanctions regime targeting Russia. Producers and consumers in this group have a shared interest in creating mechanisms to trade commodities outside the reach of the G7 financial sector. This is no small task. Dollar-denominated energy trade persists for many reasons: the dollar is liquid and freely convertible (in contrast with China’s use of capital controls and its opaque financial sector regulation) and many of the world’s largest oil exporters peg their currencies to the dollar. An expanded BRICS grouping, however, aims to pursue the energy trading that, first of all, is free from economic and financial sanctions and, second, can be carried out in their own currencies rather than in the US dollar. The vision of energy trade outlined by the BRICS states challenges the status quo of global energy markets, but the group certainly has all the necessary resources to bring this new vision into life.

The accession of Argentina will strengthen the group’s lithium supplies. Gulf powers rely heavily on investments in lithium, with Saudi Arabia having bought Brazil’s largest mining company Vale. It is expected that in their attempt to search for the new fast-growing markets Saudi Arabia along with the United Arab Emirates will invest into Argentina’s lithium. The BRICS countries’ plans to invest in Argentina’s mineral potential may cause its new president Javier Milei to reconsider the decision about leaving the group in accordance with his promises during the electoral campaign.

The membership of African nations, such as Egypt and Ethiopia, in the BRICS grouping is sure to have geopolitical consequences. From the political perspective, the expanded BRICS should serve as an effective tool for Africa to gain meaningful representation on international platforms. From the economic perspective, Egypt and Ethiopia’s huge mineral resources (oil, gas, gold, tantalite, copper, zinc) and renewable energy potential are likely to attract investment flows from the traditional Asian importers, China and India, and Persian energy powers, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Kairo is more likely to foster bilateral ties with Moscow, while Addis Ababa favors Chinese presence in its infrastructure projects.

Iran’s invitation to BRICS has a particular significance as it implies the possibility of BRICS becoming an alternative to the Western Bretton-Woods organizations. Having received a warm welcome, especially from Russia and China, Iran’s membership in BRICS will help it restore the diversity of its foreign policy through its rich natural resources (oil, gas, gold, steel, copper, iron ore) as a means to counterbalance the US sanctions.

The presence of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in BRICS is crucial, as these countries represent the strongest economies invited to join the group. They are particularly interested in boosting cooperation with dynamically growing China and India and having new markets to invest in, such as Russia, Brazil and the African nations. These countries are willing to support the BRICS de-dollarization initiatives to conduct trade in their own currencies. The agreement between India and the UAE will encourage other members to follow suit. Overall, with the addition of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran, this expanded group will include three of the world’s largest oil exporters and have 42% of global oil supply.

Oil market management will remain the purview of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and allied producers (OPEC+). In the long term, however, an expanded BRICS grouping could also play a role (Qingxin & Zhongxiu, 2020). For years, OPEC+ states have claimed that Western energy sanctions on Iran and Venezuela constrain investment and export flows. More recently, the EU embargoes on Russian seaborne crude oil and petroleum products and the EU-G7 price caps have created a new sanctions mechanism that targets revenues rather than export volumes. Other exporters worry that new sanctions tools could target them in the future, and they are wary of G7 interventions that have reshaped energy flows.

An enlarged BRICS will include oil and gas exporters and two of the largest importers, China and India—both of which refused to join the sanctions regime targeting Russia. Producers and consumers in this group have a shared interest in creating mechanisms to trade commodities outside the reach of the G7 financial sector. This is no small task. Dollar-denominated energy trade persists for many reasons: the dollar is liquid and freely convertible (in contrast with China’s use of capital controls and its opaque financial sector regulation) and many of the world’s largest oil exporters peg their currencies to the dollar. An expanded BRICS grouping, however, aims to pursue the energy trading that, first of all, is free from economic and financial sanctions and, second, can be carried out in their own currencies rather than in the US dollar. The vision of energy trade outlined by the BRICS states challenges the status quo of global energy markets, but the group certainly has all the necessary resources to bring this new vision into life.

REFERENCES

- Apergis N., Payne J. E. (2010). Natural gas consumption and economic growth: a panel investigation of 67 countries. Applied Energy, 87(8), 2759–2763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.01.002

- Backaran G., Cahill B. (2023). Six New BRICS: Implications for Energy Trade. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- Egypt Energy Agency (2022). Egypt Energy Sector: Market Report 2022. https://www.egypt-energy.com/content/dam/Informa/egyptenergy/en/pdf/Egypt%20Energy%20Report-16-5%20.pdf

- Enerdata (2022). Iran Energy Report. https://www.enerdata.net/estore/country-profiles/iran.html

- Enerdata (2023). Ethiopia Energy Report. https://www.enerdata.net/estore/country-profiles/ethiopia.html

- Hooijmaaijers B. (2021). China, the BRICS, and the limitations of reshaping global economic governance. The Pacific Review, 34(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2019.1649298

- International Energy Agency. (2020) The World Energy Outlook 2020 https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/a72d8abf-de08-4385-8711-b8a062d6124a/WEO2020.pdf

- International Energy Agency. (2022) The World Energy Outlook 2022 https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/830fe099-5530-48f2-a7c1-11f35d510983/WorldEnergyOutlook2022.pdf

- King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (2023). Saudi Arabia Energy Report. https://www.kapsarc.org/research/publications/saudi-arabia-energy-report

- Liu H., Saleem M. M., Al-Faryan M. A. S., Khan I., Zafar M. W. (2022). Impact of governance and globalization on natural resources volatility: The role of financial development in the Middle East North Africa countries. Resources Policy, 78, 102881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102881

- Ministry of Economics of Argentina (2022). National Energy Review of the Republic of Argentina. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/econom%C3%ADa/energ%C3%ADa/planeamiento-energetico/balances-energeticos

- Razzaq A., Wang Y., Chupradit S., Suksatan W., Shahzad F. (2021). Asymmetric inter-linkages between green technology innovation and consumption-based carbon emissions in BRICS countries using quantile-on-quantile framework. Technological Society, 66, 33–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101656

- Qingxin L., Zhongxiu Z. (2020). Promoting BRICS cooperation for economic growth and development. Revista Tempo do Mundo, (22), 39–58.

- United Arab Emirates Ministry of Energy and Industry (2022). The United Arab States Energy Report. https://www.moei.gov.ae/en/open-data.aspx

- Valizadeh A., Houshialsadat S. M. (2013). Iran and the BRICS: The Energy Factor. Iranian Review of Foreign Affairs, 4. 165–190.

- Wilson J. D. (2015). Resource powers? Minerals, energy and the rise of the BRICS. Third World Quarterly, 36(2), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1013318

- Yu Z., Liu W., Chen L., Eti S., Dinçer H., Yüksel S. (2019). The effects of electricity production on industrial development and sustainable economic growth: A VAR analysis for BRICS countries. Sustainability, 11 (21), 5895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215895

Keywords: BRICS, the expansion of BRICS, energy markets, global energy trade, oil and gas, renewable energy